Published on Franz Liszt Group, on June 7, 2021. If you want to know how the Story Behind series started, I give details in “Story Behind” Series #1″.

Original post:

My piano is to me what a ship is to the sailor, what a steed is to the Arab. It is the intimate personal depository of everything that stirred wildly in my brain during the most impassioned days of my youth. It was there that all my wishes, all my dreams, all my joys, and all my sorrows lay.

Franz Liszt

Conversation and story behind:

Diane Kolin

Hello friends. Here we have both Young Liszt and Old Liszt. Time for a new “story behind”

The quote was written by Liszt to his friend Adolphe Pictet, a Swiss linguist, philologist and ethnologist, in Chambéry in September 1837. It was first published by Liszt himself in the French Musical Journal in which he was frequently writing, the Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris, on February 11, 1838. In this journal, Liszt published a series of letters under the name “Lettres d’un bachelier ès musique” (known, in English, as “An Artist’s Journey”). In these letters, he is writing to his friends to explain what music means to him. The quote in this post is a perfect illustration of the kind of content that could be found in these writings. Lina Ramann mentioned these quote and letter in the first part of her biography of Liszt (English translation: “Franz Liszt, Artist and Man, 1811-1840”, Volume 2), in German. Then the whole set of original French letters was published. You can find all the letters of “An Artist’s Journey” in an English translation of 1989 by Charles Suttoni, in University of Chicago Press. I highly recommend them. There are 16 letters in total, addressed to George Sand, Hector Berlioz, and other important figures of Liszt’s circle in the 1830s and 40s.

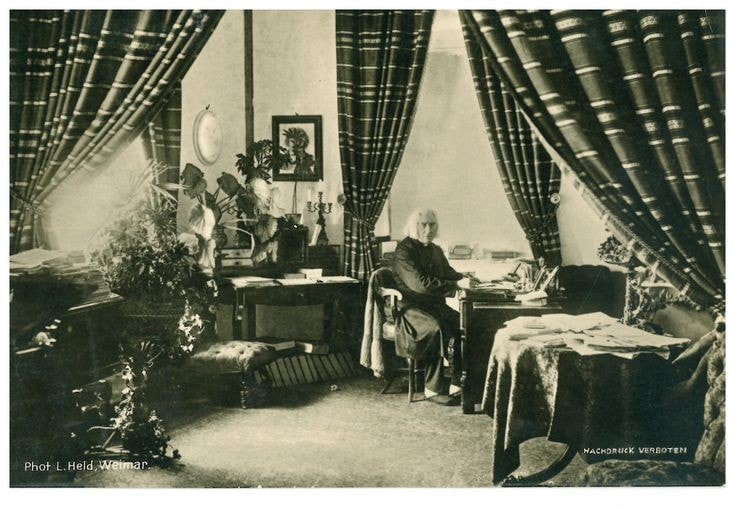

The picture is a famous one of Old Liszt taken by Louis Held, who was a frequent guest in 1884 and 1885 to photograph the Master and his pupils. Here, you can see him at his writing desk in June 1884 in his house in Weimar, the Hofgärtnerei. Today, when you visit the Liszt-Haus in Weimar, the furniture, portraits, and desks are still at the exact same place. A few weeks ago, a picture was posted representing Liszt siting in a park with his pupil Carl Lachmund and wife Caroline Lachmund. This one was also taken by Louis Held in 1884. Lachmund wrote a very detailed journal about his years studying with Liszt, from 1882 to 1884, “Living with Liszt”, in which he wrote about the day the picture was taken. Despite the serious look (which is not rare for Liszt in pictures), he was in a good mood and decided to accept Held’s request to have him sitting at his desk for a picture. Caroline and Carl were also present. Caroline took care of Liszt’s hair, and Carl arranged the books – he placed volumes by Bach and Beethoven on the piano so that the names could be recognized (we can see the scores on the piano on the left). Lachmund related that Liszt had to stay still for a full minute so that the picture could be taken.

Group member:

Lachmund’s diary is indeed excellent reading, both for its descriptions of Liszt, as well as his impressions of his fellow students, some of whom would go on to become the greatest pianists of their generation. Along the same lines, I also recommend heartily the reminiscences of Arthur Friedheim and Siloti. The better-known diary of Amy Fay, which recounts the second Weimar period of the 1870s, is also interesting reading, particularly as she compares and contrasts Liszt, Tausig, and Rubinstein. Additionally, and likely most significantly, Rosenthal wrote his memoirs, which were housed in manuscript in the Mannes School of Music, but recently published, I believe. Rosenthal, who was held in great esteem by Liszt, asserts that Liszt’s famed youthful crisis upon hearing Paganini, which sent him practicing for twelve hours a day, was something of a myth. It was not Paganini, but none other than Chopin, who precipitated the crisis. Liszt, according to Rosenthal, told the latter that he could not bring himself to publicly admit that it was another pianist that drove him into such intense study!

Diane Kolin:

Absolutely

Amy Fay wrote “Music-study in Germany” in 1913. She spent part of the year 1873 as his student and described in details what it was to be Liszt’s pupil. As Andrew Gentile said, this one is not only about Liszt but about the very rich German musical life: Tausig, Clara Schumann, Joachim, Rubinstein, Kullak, Wagner, von Bülow, Deppe…

As for Siloti and Friedheim, both tell their life as one of the Master’s students during the last years of his life, with a lot of discussions about the pieces they were practicing with him and how the masterclasses were organized. In 1986 a book called “Remembering Franz Liszt” was published, containing both journals in English.

Alexander Siloti wrote “My Memories of Liszt”, first published in German in 1903. It is a short but pretty complete report on his life in Weimar.

Arthur Friedheim wrote “Life and Liszt”, first published in English in 1961. He started studying with Liszt in 1879, until he died in 1886. It is a journal, but it also tells the reader about Liszt’s life, his correspondence, his writings… Very interesting book.

In the students’ writings about Liszt in old age as a teacher, there are also the memories of August Stradal, who published some score sketches by Liszt and pictured the man and the teacher, and August Göllerich, who listed all the pieces performed by the students during the masterclasses from 1884 to 1886, with comments and directions by Liszt.

To learn about the earlier masterclass period, when Liszt was in his 40s, Liszt’s student William Mason wrote “Memories of a musical life”, published in 1900, in which he relates his life in America and in Europe. A good part of the book is about his studies with Liszt in Weimar during two years, from 1853 to 1854. After Mason left, they wrote to each other until a few days before Liszt died. But in this book, like Amy Fay did, he also talk about Moscheles, Wagner, Schumann, Joachim, Chopin, Thalberg, Rubinstein, and other musical personalities of the time he was in Germany.

Keep reading

(Note: Isn’t it fabulous to exchange references? The conversation continued and other references were given but the topic became focused on another subject.)