Since the summer is over, I wanted to publish a new “story behind” before my schedule gets too busy with my Fall 2022 activities. Instead of a story based on a photograph of Liszt, I propose the story behind a statue of Liszt, which can be seen where I live, in the city of Toronto in Canada.

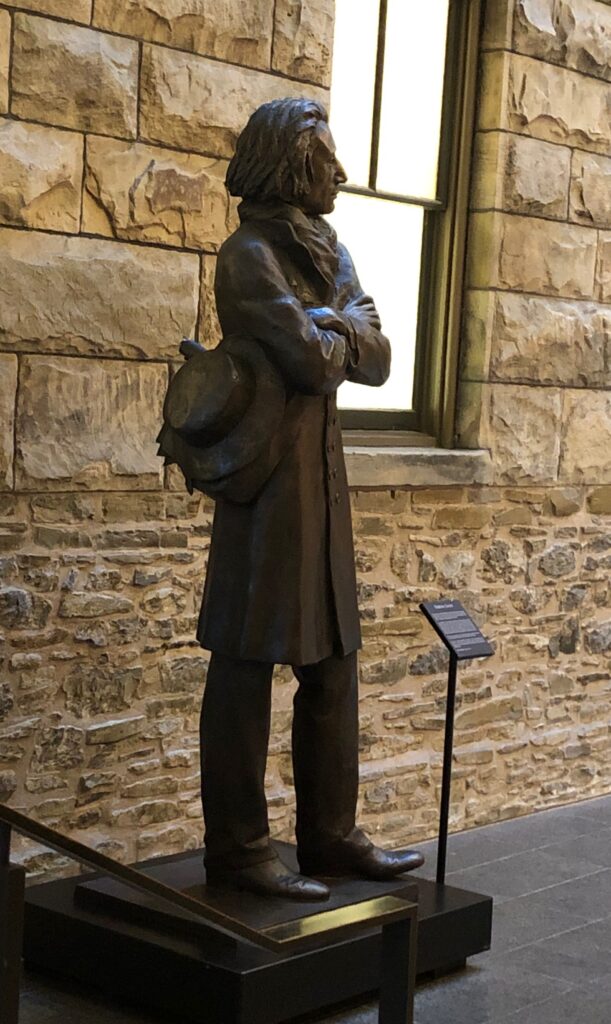

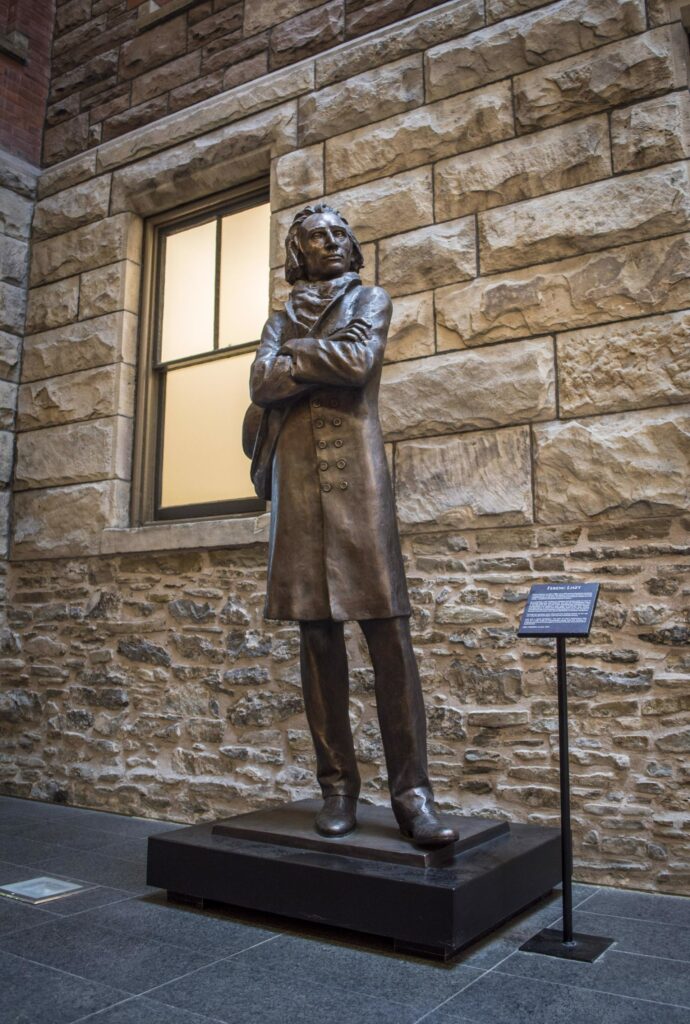

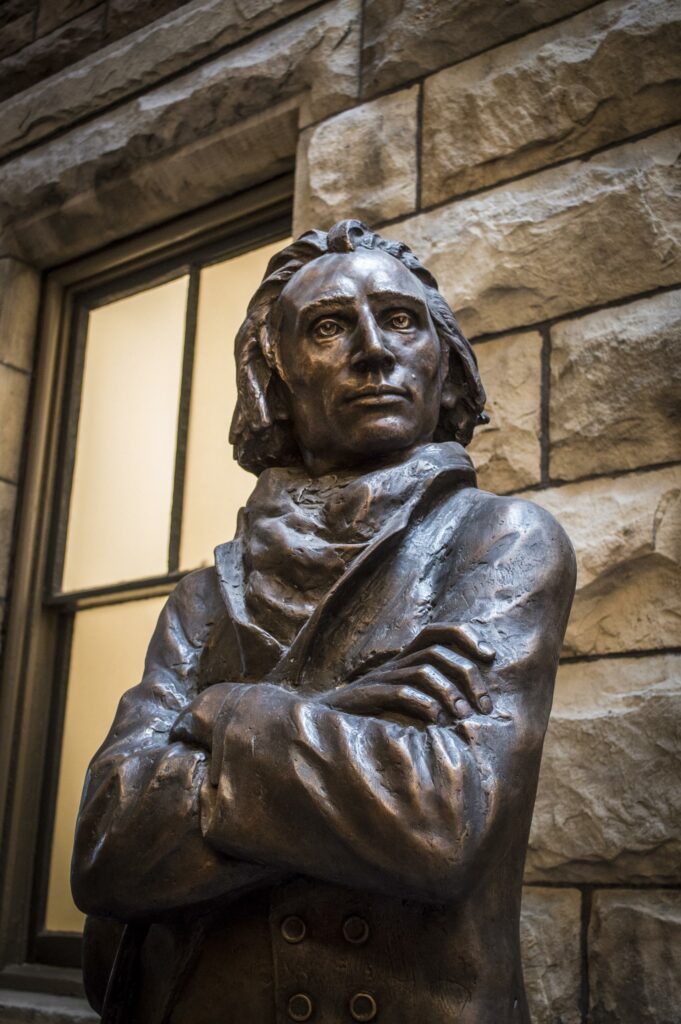

Recently, I was at Toronto’s famous concert hall, Koerner Hall, part of the Royal Conservatory of Music (now called Oscar Peterson School of Music), for a rehearsal. Somewhere in the building, a statue of Liszt can be admired. I posted pictures on social media. Intrigued, some of my Lisztian friends in France asked for more details.

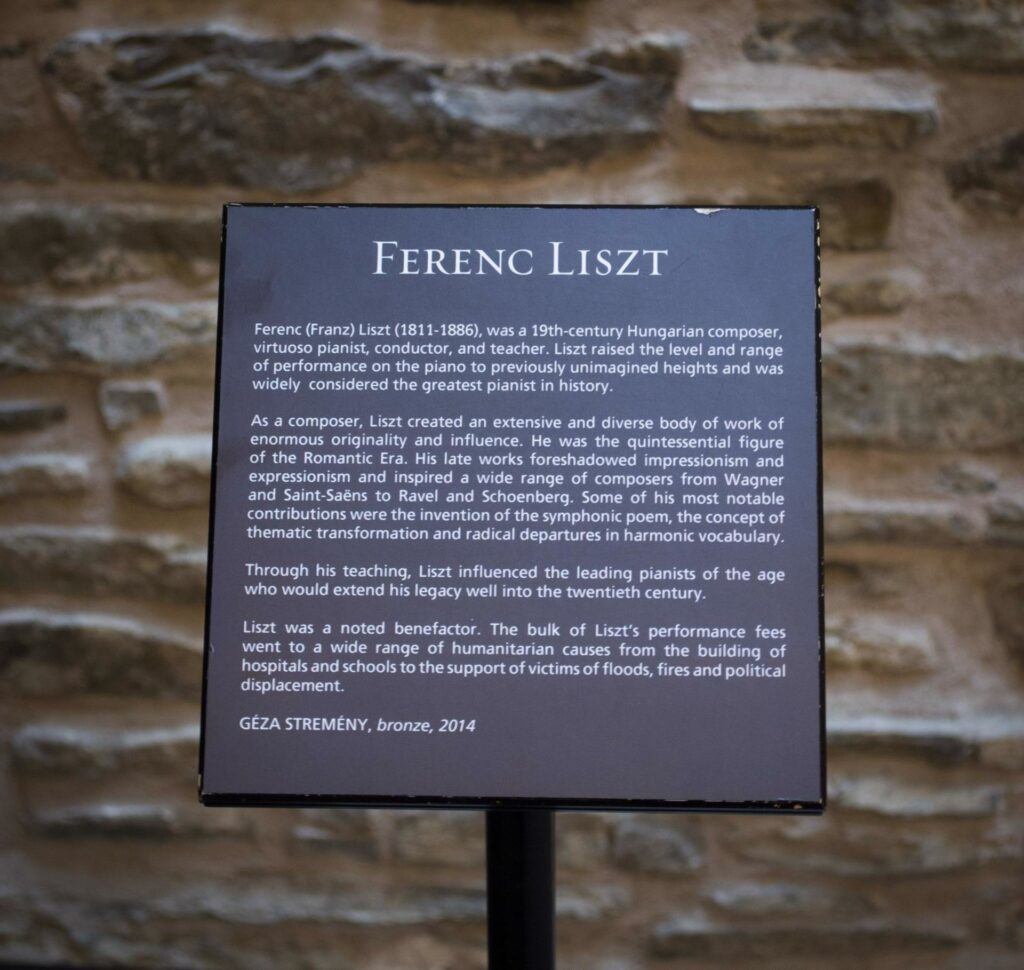

This statue is a 7 feet (2.25m) tall sculpture. It was offered to the Royal Conservatory of Music in 2014 by the Canadian-Hungarian donor Tamás Fekete, who also made a gift of a bronze statue of Béla Bartók to the school a few years before. The Liszt sculpture was commissioned to a Hungarian artist, Géza Stremeny, who is famous for his statues of Hungarian Prime Minister Count István Bethlen in Buda Castle and Count Lajos Batthyány, head of the country’s first government, on the Budapest square bearing his name. The Liszt statue was transported to Canada by air, where it was unveiled in the Conservatory building. At the ceremony one of the speakers was the Canadian Liszt expert Alan Walker, known for his very complete biography of Franz Liszt in three volumes. (1)

The Royal Conservatory of Music, first called Toronto Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886, the year Liszt died. Dr. Peter Simon, who was appointed President of The Royal Conservatory in September 1991 and is still CEO of the school today, is a Hungarian-born Canadian.

In his biography, Alan Walker tells the story of a portrait of Liszt that made his way to Toronto as a gift from the composer to the piano factory Mason & Risch. I reproduce here the full excerpt (2):

Paul von Joukowsky (…), who was still basking in praise for his stage designs for Parsifal, had followed Liszt from Bayreuth [in 1882] in order to paint his portrait. The picture had been commissioned by Liszt himself as a gift to the piano manufacturer Vincent Risch, who had recently met Liszt and had presented him with one of the first grand pianos made by his Toronto-based firm, Mason and Risch.

Note 16: Although the firm of Mason and Risch had long been making upright and square pianos, they had never made grands. At Liszt’s encouragement they produced their first model in April 1882. Risch was delighted with the result, and he told Liszt that it was notable for its richness, breadth, and power. When Liszt expressed interest in testing the instrument, Risch sent him a second model, which was delivered to Weimar on September 19, 1882. After playing on it for more than two months, Liszt told Risch: “The Mason & Risch grand piano you forwarded to me is excellent, magnificent, unequalled. Artists, Judges, and the Public will certainly be of the same opinion.” (This letter, which is dated November 10, 1882, is reproduced in a Mason & Risch advertisement in the Toronto Globe for December 18, 1883.) Liszt eventually gave the instrument to Carl Gille. (See LL, pp. 156–57.)

Liszt had already granted Joukowsky a number of sittings. By the end of the year the picture was finished, and all who saw it were struck by its vivid likeness to the composer. Joukowsky was prevailed upon by Carl Alexander to make a copy for deposit in the Weimar art gallery, which necessitated a short delay before the original could be despatched to Toronto. When it arrived, Risch had it hung in his showrooms, where it generated intense local interest.

Note 17: The picture arrived in Toronto on September 5, 1883. Vincent Risch told Liszt: “For weeks Toronto society came in their thousands to our hall, with their hats off and as serious as if they were in church. Men come and gaze on those well-known, admired, and venerated features.… This portrait, so strikingly natural, established the talent of the artist, and makes us all feel that you, dear master, are in our midst; and Canada feels richer and happier at the thought of possessing you.…” (WFLR, pp. 189–90) See also Liszt’s letter on this topic to Risch. (LLB, vol. 2, p. 346)

The firm of Mason and Risch continued to make capital out of the Liszt portrait for a number of years. At the Toronto Exhibition of 1887 their booth was dominated by the painting, given to them “in acknowledgement of the excellence of a pianoforte sent to [Liszt] at Weimar by these gentlemen.” (Toronto Daily Mail, September 10, 1887)

The portrait remained in the Toronto showroom until after World War II, when the firm went into liquidation. Meanwhile, the painting has passed into private ownership in America. (It was often wrongly attributed to the Toronto Conservatory of Music, who were never its owners.) Fortunately, the firm of Alfred Krupp, in Essen, made a good likeness of the picture which has made its way into many of the Liszt iconographies (see BFL, p. 286). And what became of the second canvas that Joukowsky painted for the grand duke? This, too, found its way to Vincent Risch in Toronto, and was exhibited by him at the Colonial Exhibition in London in the summer of 1886. This painting, which is now in the possession of a private owner in southern Ontario, was only identified in 1993. (3)

An even more detailed report of 25 pages about the relationship between Liszt and the piano factory has been published by Geraldine Keeling in her chapter entitled “Liszt and Mason & Risch” in New Light on Liszt and His Music: Essays in Honor of Alan Walker’s 65th Birthday. (4) The article gives many details about the firm and the two men behind the name. More basic information can be found about Mason & Risch here:

- Carl Morey, The Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited 13 December 2013. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/mason-risch-emc

- Antique Piano Shop. https://antiquepianoshop.com/online-museum/mason-risch/. The page contains pictures of advertisements and one of the firm’s pianos.

(1) György Lázár, “Liszt statue in Toronto.” Hungarian Free Press, 25 December 2014. https://hungarianfreepress.com/2014/12/25/liszt-statue-in-toronto/

(2) Alan Walker, Franz Liszt Volume 3: The final years, 1861-1886. Knopf, 1996. Chapter: Nuages gris. III.

(3) The acronyms used in the notes are the followings:

BFL: Burger, Ernst. Franz Liszt: A Chronicle of His Life in Pictures and Documents. Translated by Stewart Spencer. Princeton, 1989.

LL: Living with Liszt: The Diary of Carl Lachmund, an American pupil of Liszt, 1882–1884. Edited, annotated, and introduced by Alan Walker. Stuyvesant, N.Y., 1995.

LLB: La Mara, ed. Franz Liszts Briefe. 8 vols. Leipzig, 1893–1905. 1: Von Paris bis Rom. 2: Von Rom bis ans Ende. 3: Briefe an eine Freundin. 4, 5, 6, 7: Briefe an die Fürstin Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein. 8: Neue Folge zu Band I und II.

WFLR: Wohl, Janka. François Liszt: Recollections of a Compatriot. Translated by B. Peyton Ward. London, 1887.

(4) Michael Saffle and James Deaville, Analecta Lisztiana II: New Light on Liszt and His Music: Essays in Honor of Alan Walker’s 65th Birthday. Pendragon Press, 1997.